Read former Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument intern J.J. Huie’s full article in the Spring 2008 Friends newsletter!

With Deep Roots in Colorado: The Ponderosa Pine

by J.J. Huie

I like running in Colorado when the sound of my breathing is drowned out by a wind so violent it causes the arms of the ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa) to thrash about wildly. Hundreds of miles from the Pacific, in the foothills next to Rampart Range near Colorado Springs, I feel like I’m sailing through an ocean storm. In crossing this ocean, however, there is no salty scent or giant, looming swells; instead, I have the waving motion of the ponderosas and the rich aroma they exude.

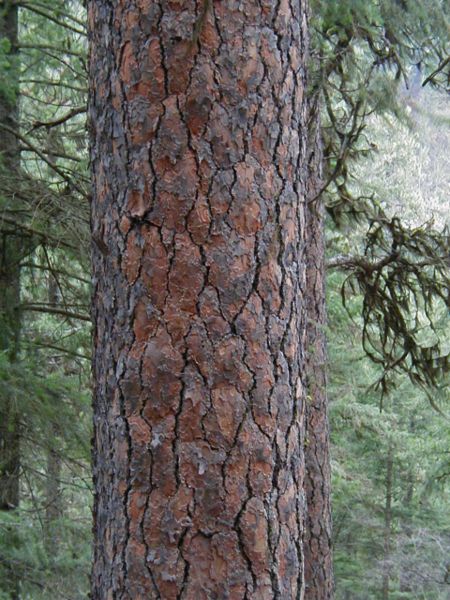

In Colorado, the ponderosa pine ecosystem can be found at an elevation range of 5,600 feet to 9,000 feet on both sides of the Continental Divide, with ponderosas dominating on sunny, south-facing slopes. Throughout much of the elevation range of the ponderosa, Douglas-firs predominate on the shadier, north-facing slopes. Direct solar radiation is critical to the ponderosa, which germinates best on soils with unobstructed sunlight. Standing close to a mature tree, I enjoy the scent of vanilla that the orange-brown bark gives off as it’s warmed by the sun.

A distinctive feature of ponderosas is their long needles (up to 7 inches in length), which come in bundles of two or three needles. The needles of ponderosas are the longest among conifers in Colorado. Some ponderosas are among the largest trees in the Southern Rockies (the area from southern Wyoming through Colorado to northern New Mexico), growing up to 150 feet in height and more than 3 feet in diameter.

Mature trees usually have rounded crowns, while the oldest trees can have flat-topped crowns, unlike most other conifer species. Mature cones are globe shaped and can be up to 6 inches long; each of the cone’s thick scales is tipped with a sharp bristle.

We normally don’t see one of the most amazing features of the ponderosa: the tree’s extensive root system, an adaptation to frequent drought. Ponderosa pine forests typically receive from about 16 inches of precipitation in New Mexico and south-central Colorado to more than 25 inches in areas of Wyoming. While above average moisture in spring and early summer allows for seedling establishment, seedlings quickly develop a long taproot which helps them survive drought that dries out the topsoil. Mature ponderosas have taproots that can reach depths of up to 40 feet and lateral roots that extend through surface soils as much as 100 feet from the tree. I’ve marveled at how ponderosas stand up against Colorado’s sometimes vicious winds, but with such a wide-spreading root system, it’s difficult for a ponderosa to be shaken at its depths.

We normally don’t see one of the most amazing features of the ponderosa: the tree’s extensive root system, an adaptation to frequent drought. Ponderosa pine forests typically receive from about 16 inches of precipitation in New Mexico and south-central Colorado to more than 25 inches in areas of Wyoming. While above average moisture in spring and early summer allows for seedling establishment, seedlings quickly develop a long taproot which helps them survive drought that dries out the topsoil. Mature ponderosas have taproots that can reach depths of up to 40 feet and lateral roots that extend through surface soils as much as 100 feet from the tree. I’ve marveled at how ponderosas stand up against Colorado’s sometimes vicious winds, but with such a wide-spreading root system, it’s difficult for a ponderosa to be shaken at its depths.

Low-intensity fires initiated by lightning during the summer were an important part of the ponderosa pine ecosystem before logging and wildfire suppression. Wildfires kill smaller plants and thin out dense stands of seedlings, decreasing competition for moisture. In addition, fires release nutrients in the litter of needles and twigs on the ground, thereby increasing the fertility of the soil. The thick bark of mature ponderosas provides protection against fires; nonetheless, the reduction in fuel loads that occurs with low-intensity fires is necessary to prevent catastrophic fires which could kill even mature trees. Since the beginning of the 1900s, fire suppression and logging have allowed other conifers to establish themselves in ponderosa forests or caused increased regeneration of ponderosas. The result has been overcrowded forests and smaller, less robust ponderosa pines.

The ponderosa pine’s affinity for sunny, south-facing slopes, extensive root system, and adaptations to the lightning-induced fires that spread more quickly under dry, windy conditions, reveal a high degree of adaptation. The species has even developed defenses against the pine beetle, including a higher concentration of limonene, a chemical toxic to the pine beetle, in ponderosas that survived infestations. Beyond its ability to withstand oftentimes harsh conditions, the ponderosa never ceases to bring pleasure to those who venture into the woods, whether we find a shady place under its sweeping branches, hear the music of its long needles fluttering against a cool breeze, or simply stand close for the scent of vanilla.

Photo Credits: Walter Siegmund (ponderosa needles and cones), Jamie Dwyer/public domain (ponderosa trunk)